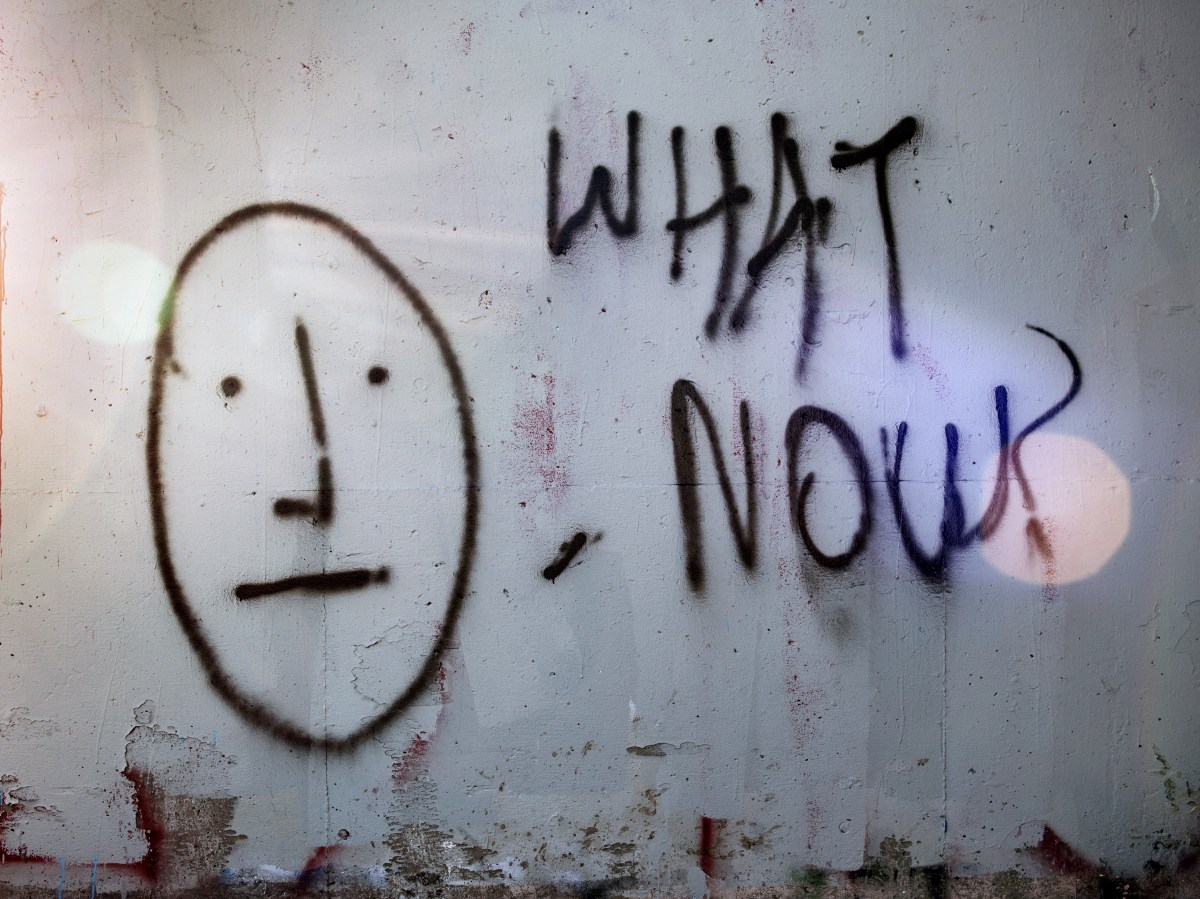

It’s easy to fall into the trap of Analysis Paralysis, endlessly reviewing decisions and never actually doing something.

If you find yourself doing that, then you can break out of the loop by trying to go with your gut.

Don’t spend forever building the decision up, but think about what feels good, and go with that.

It’s best to use this approach for smaller decisions, especially in areas that you are familiar with or that give you an option to undo if really necessary. It’s a topic I’ve written about before, but it’s really useful to remember that there are very few decisions that are truly irreversible.

If it feels a bit overwhelming, break up choices into smaller decisions. One thing that often drives the paralysis is the scope or the implication that you feel of the decision. Don’t get hung up on the colour scheme of your entire house, just paint a room in a colour you like the feeling of. If it looks good, great! If not, it’s a smaller investment to correct than having done the whole building.

When we look to our gut, it’s good to run a few checks before really trusting it. Is this an area that you are confident in? Is it really a familiar space for you to make a decision? Is there a way to make it smaller or easier?

Finally, check your bias. Especially in cases where it’s a decision related to people not things. If you like a particular way of doing things, or are comfortable with an approach, make sure you aren’t layering that bias onto the decision. Challenge this with a quick checklist or a way to score performance. Sometimes you break the paralysis by having the tools in hand to make the decision before you are called to think about it.

So, if you find yourself getting stuck, find some opportunities to make quick decisions and measure the outcome, and use this to hone your approach to make a choice faster.

No decision is still a decision, and don’t let Analysis Paralysis force the non-choice upon you by default!